John Cobb (motorist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Rhodes Cobb (2 December 1899 – 29 September 1952) was an early to mid 20th century

Driving the piston-engined, wheel-driven

Driving the piston-engined, wheel-driven

After the 1947 achievement, Cobb turned his mind to becoming on water what he now was on land and went after the simultaneous World Water Speed Record. He commissioned from '' Vospers'' the jet-engine powered speedboat '' Crusader'' and selected the long water loch of

After the 1947 achievement, Cobb turned his mind to becoming on water what he now was on land and went after the simultaneous World Water Speed Record. He commissioned from '' Vospers'' the jet-engine powered speedboat '' Crusader'' and selected the long water loch of

John Cobb married Elizabeth Mitchell-Smith in 1947. Elizabeth died from

John Cobb married Elizabeth Mitchell-Smith in 1947. Elizabeth died from

The Reluctant Hero by David Tremayne

*

Location and Google Street View

of John Cobb Memorial * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cobb, John Segrave Trophy recipients BRDC Gold Star winners Land speed record people Water speed records Brooklands people English racing drivers British motorboat racers Brighton Speed Trials people Recipients of the Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct Air Transport Auxiliary pilots Royal Air Force officers British World War II pilots People from Esher People educated at Eton College 1899 births 1952 deaths Bonneville 300 MPH Club members Motorboat racers who died while racing Sport deaths in Scotland Grand Prix drivers Filmed deaths in motorsport

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

racing motorist. He was three times holder of the World Land Speed Record

The land speed record (or absolute land speed record) is the highest speed achieved by a person using a vehicle on land. There is no single body for validation and regulation; in practice the Category C ("Special Vehicles") flying start regula ...

, in 1938, 1939 and 1947, set at Bonneville Speedway

Bonneville Speedway (also known as the Bonneville Salt Flats Race Track) is an area of the Bonneville Salt Flats northeast of Wendover, Utah, that is marked out for motor sports. It is particularly noted as the venue for numerous land speed recor ...

in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, US. He was awarded the Segrave Trophy

The Segrave Trophy is awarded to the British national who demonstrates "Outstanding Skill, Courage and Initiative on Land, Water and in the Air". The trophy is named in honour of Sir Henry Segrave, the first person to hold both the land and wat ...

in 1947. He was killed in 1952 whilst piloting a jet powered speedboat attempting to break the World Water Speed Record on Loch Ness

Loch Ness (; gd, Loch Nis ) is a large freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands extending for approximately southwest of Inverness. It takes its name from the River Ness, which flows from the northern end. Loch Ness is best known for clai ...

water in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

.

Early life

Cobb was born inEsher

Esher ( ) is a town in Surrey, England, to the east of the River Mole.

Esher is an outlying suburb of London near the London-Surrey Border, and with Esher Commons at its southern end, the town marks one limit of the Greater London Built-Up Ar ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

, on 2 December 1899, near the Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields, ...

motor racing track which he frequented as a boy. He was the son of Florence and Rhodes Cobb, a wealthy furs broker in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

. He received his formal education at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

and Trinity Hall, Cambridge

Trinity Hall (formally The College or Hall of the Holy Trinity in the University of Cambridge) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

It is the fifth-oldest surviving college of the university, having been founded in 1350 by ...

, before joining his father's firm and pursuing a successful career as the managing director of a number of companies in the trade, the personal financial resources from which he used to fund a passion for large capacity motor high speed racing. In 1924 he acquired a Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

aviator's certificate, qualifying as a pilot on a Sopwith Grasshopper

__NOTOC__

The Sopwith Grasshopper was a British two-seat touring biplane built by the Sopwith Aviation and Engineering Company at Kingston upon Thames in 1919.Jackson 1974, p. 309

Development

The Grasshopper was a conventional two-seat open-c ...

.

Racing and speed records career

Cobb won his first track race in a 1911 10-litre Fiat in 1925, and raced in theHigham Special

Chitty Bang Bang was the informal name of a number of celebrated British racing cars, built and raced by Count Louis Zborowski and his engineer Clive Gallop in the 1920s, which inspired the book, film and stage musical ''Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Ban ...

at Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields, ...

race track in 1926.

In 1928 he privately purchased a 10.5-litre ''Delage

Delage was a French luxury automobile and racecar company founded in 1905 by Louis Delâge in Levallois-Perret near Paris; it was acquired by Delahaye in 1935 and ceased operation in 1953.

On 7 November 2019, the association "Les Amis de Dela ...

'' which was imported to England from the factory in Paris, which he raced at Brooklands from 1929 to 1933, breaking the flying start outer lap Record three times in these years, and being clocked at a top speed of 138.88 miles per hour on 2 July 1932. In 1932 he also won the British Empire Trophy at Brooklands.

In 1933 he privately commissioned the design and construction of the 24-litre " Napier Railton" from "Thomson & Taylor

Thomson & Taylor were a motor-racing engineering and car-building firm, based within the Brooklands race track. They were active between the wars and built several of the famous land speed record breaking cars of the day.

Thomas Inventions Devel ...

", with which he broke a number of track speed records, including setting the ultimate lap record at the Brooklands race track which was never surpassed, driving at an average speed of achieved on 7 October 1935, having earlier overtaken the 1931 record set by Sir Henry "Tim" Birkin driving Bentley Blower No.1, and regaining it from his friend Oliver Bertram

Oliver Henry Julius Bertram (26 February 1910 – 13 September 1975) was an English racing driver who held the Brooklands race track record for 2 months 2 days during 1935. He was twice awarded the BRDC Gold Star. He was also a Barrister-At-Law ...

. In the 1934 RAC Tourist Trophy

The RAC Tourist Trophy (sometimes called the International Tourist Trophy) is a motor racing award presented by the Royal Automobile Club (RAC) to the overall victor of a motor race in the United Kingdom. Established in 1905, it is the world's ol ...

race on the Ards Circuit

The Ards Circuit was a motorsport street circuit in Northern Ireland used for RAC Tourist Trophy sports car races from 1928 until 1936, when eight spectators died in an accident. Industrialist and pioneer of the modern agricultural tractor, Har ...

near Belfast the Lagondas of Cobb and the Hon Brian Lewis competed in the class for larger sports cars against Eddie Hall

Edward Stephen Hall (born 15 January 1988) is an English media personality, actor, boxer, and former strongman.

He won the World's Strongest Man 2017 competition. Hall has also won national competitions such as UK's Strongest Man, Britain's S ...

in a Bentley.

Driving the piston-engined, wheel-driven

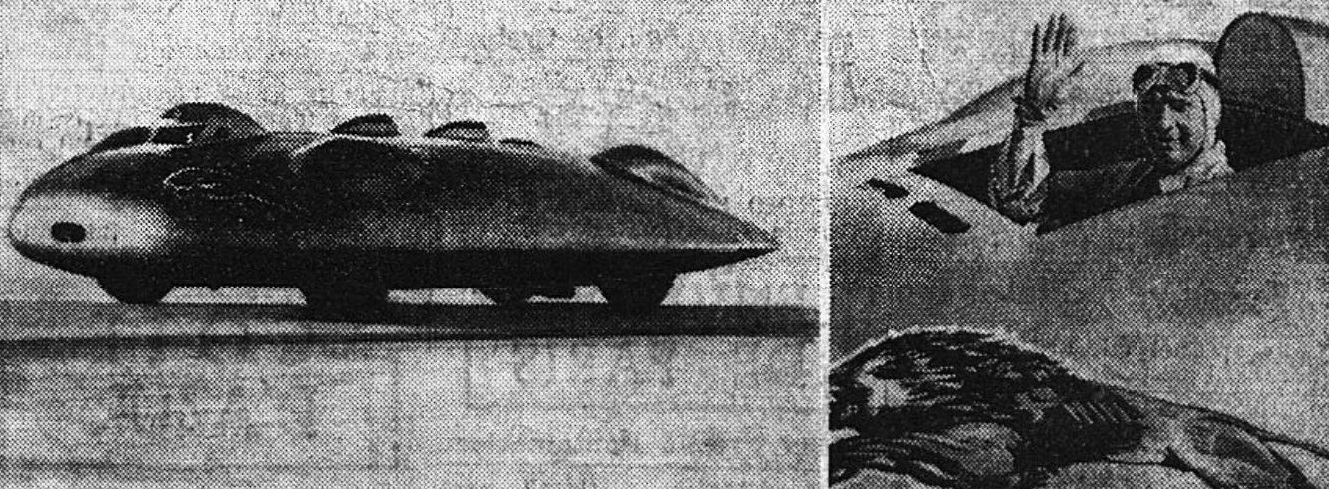

Driving the piston-engined, wheel-driven Railton Special

The ''Railton Special'', later rebuilt as the ''Railton Mobil Special'', is a one-off motor vehicle designed by Reid Railton and built for John Cobb's successful attempts at the land speed record in 1938.

It is currently on display at Thinkt ...

, he broke the World Land Speed Record

The land speed record (or absolute land speed record) is the highest speed achieved by a person using a vehicle on land. There is no single body for validation and regulation; in practice the Category C ("Special Vehicles") flying start regula ...

at Bonneville salt flats

The Bonneville Salt Flats are a densely packed salt pan in Tooele County in northwestern Utah. A remnant of the Pleistocene Lake Bonneville, it is the largest of many salt flats west of the Great Salt Lake. It is public land managed by the Bur ...

on 15 September 1938 by achieving 350 miles per hour. He broke it a second time at the same site on 23 August 1939, achieving 369 miles per hour.

War service

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he served as a pilot in the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, and between 1943 and 1945 served with the Air Transport Auxiliary

The Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) was a British civilian organisation set up at the start of the Second World War with headquarters at White Waltham Airfield in Berkshire. The ATA ferried new, repaired and damaged military aircraft between factori ...

, being demobilised with the rank of Group Captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

. He made an (uncredited) appearance in the wartime propaganda film ''Target for Tonight

''Target for Tonight'' (or ''Target for To-Night'') is a 1941 British World War II documentary film billed as filmed and acted by the Royal Air Force, all during wartime operations. It was directed by Harry Watt for the Crown Film Unit. The fi ...

'' (1941).

Post-war speed record career and death

Cobb returned toBonneville salt flats

The Bonneville Salt Flats are a densely packed salt pan in Tooele County in northwestern Utah. A remnant of the Pleistocene Lake Bonneville, it is the largest of many salt flats west of the Great Salt Lake. It is public land managed by the Bur ...

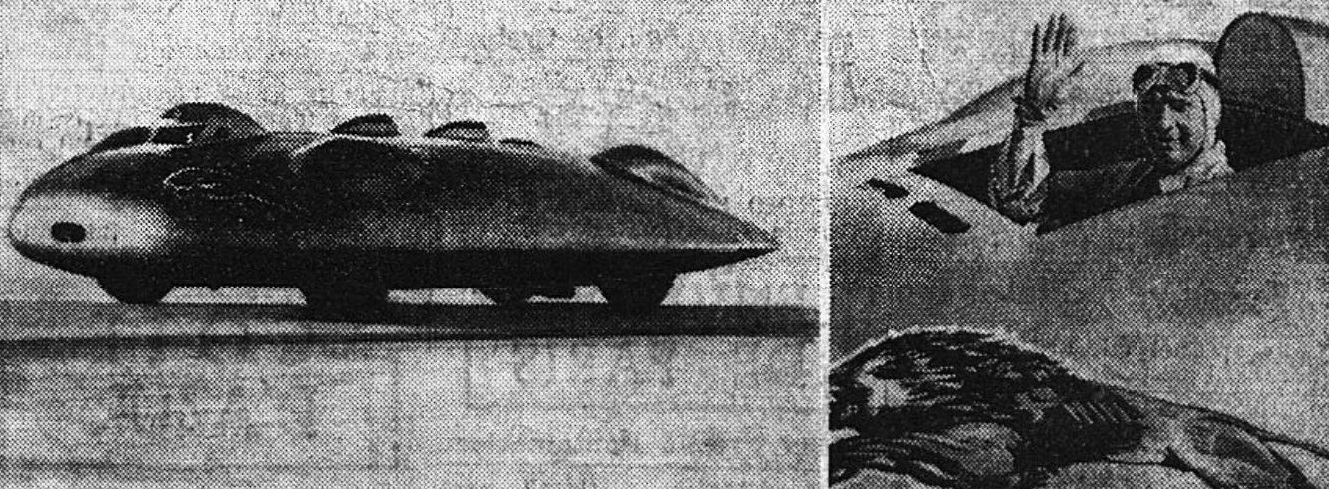

again in 1947, where on 16 September he beat his own standing 1939 World Land Speed Record by reaching (on one of the two runs he was clocked at having reached ), earning him the press moniker

"The Fastest Man Alive". This record remained in place until 1963, when it was surpassed by the American Craig Breedlove

Craig Breedlove (born March 23, 1937) is an American professional race car driver and a five-time world land speed record holder. He was the first person in history to reach , and , using several turbojet-powered vehicles, all named '' Spirit o ...

.

After the 1947 achievement, Cobb turned his mind to becoming on water what he now was on land and went after the simultaneous World Water Speed Record. He commissioned from '' Vospers'' the jet-engine powered speedboat '' Crusader'' and selected the long water loch of

After the 1947 achievement, Cobb turned his mind to becoming on water what he now was on land and went after the simultaneous World Water Speed Record. He commissioned from '' Vospers'' the jet-engine powered speedboat '' Crusader'' and selected the long water loch of Loch Ness

Loch Ness (; gd, Loch Nis ) is a large freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands extending for approximately southwest of Inverness. It takes its name from the River Ness, which flows from the northern end. Loch Ness is best known for clai ...

in Scotland for the speed trial. On 29 September 1952 he was killed at the age of 52 whilst attempting to break the world Water Speed Record at Loch Ness whilst piloting ''Crusader'' at a speed in excess of . During the run the boat hit an unexplained wake in the water and disintegrated about Cobb. The 1975 Sunn Classic Pictures documentary ''The Mysterious Monsters'' offered the theory that the wake was caused by the Loch Ness Monster, or Nessie as it is called, trying to get out of the way of Cobb's boat. His body, which had been thrown beyond the wreckage, was recovered from the loch, and subsequently conveyed back to his home county of Surrey, where it was buried in the graveyard of Christ Church, Esher. A memorial was subsequently erected on the Loch Ness shore to his memory by the townsfolk of Glenurquhart

Glenurquhart or Glen Urquhart ( gd, Gleann Urchadain) is a glen running to the west of the village of Drumnadrochit in the Highland council area of Scotland.

Location

Glenurquhart runs from Loch Ness at Urquhart Bay in the east to Corrimon ...

.

In 2002 the remains of the jet engine speedboat ''Crusader'' were located on the bed of Loch Ness at a depth of and the site was designated as a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

in 2005. The wreck was filmed by a research team from National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widely ...

in 2019.

Personal life

John Cobb married Elizabeth Mitchell-Smith in 1947. Elizabeth died from

John Cobb married Elizabeth Mitchell-Smith in 1947. Elizabeth died from Bright's Disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied b ...

14 months later. In 1950 he married Vera Victoria Henderson (1917–2007).

Cobb resided at 'Grove House' in Esher, an 18th-century mansion, which was demolished in the late 20th century for building development. A public green in Esher (located at 51.37933 -0.36472) was named 'Cobb Green' in tribute to his achievements. In 2013 an archaeological excavation of meadowland at Arran Way at Esher's Lower Green uncovered the foundations of Grove House. In 2017 a Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

was unveiled by Richard Noble

Richard James Anthony Noble, OBE (born 6 March 1946) is a Scottish entrepreneur who was holder of the land speed record between 1983 and 1997. He was also the project director of ThrustSSC, the vehicle which holds the current land speed record ...

to Cobb's memory at the newly re-built Cranmere Primary School which partially occupies the site of the former Grove House estate.

Awards

* British Empire Trophy (1932). *Segrave Trophy

The Segrave Trophy is awarded to the British national who demonstrates "Outstanding Skill, Courage and Initiative on Land, Water and in the Air". The trophy is named in honour of Sir Henry Segrave, the first person to hold both the land and wat ...

(1947).

* Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct

The Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct, formerly the King's Commendation for Brave Conduct, acknowledged brave acts by both civilians and members of the armed services in both war and peace, for gallantry not in the presence of an enemy. Est ...

(1953).John Rhodes Cobb (deceased), Racing Motorist. For services in attempting to break the world's water speed record, and in research into high speed on water, in the course of which he lost his life.

References

Citations Bibliography *External links

The Reluctant Hero by David Tremayne

*

Location and Google Street View

of John Cobb Memorial * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cobb, John Segrave Trophy recipients BRDC Gold Star winners Land speed record people Water speed records Brooklands people English racing drivers British motorboat racers Brighton Speed Trials people Recipients of the Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct Air Transport Auxiliary pilots Royal Air Force officers British World War II pilots People from Esher People educated at Eton College 1899 births 1952 deaths Bonneville 300 MPH Club members Motorboat racers who died while racing Sport deaths in Scotland Grand Prix drivers Filmed deaths in motorsport